In the NFL’s 2021 season opener, the Dallas Cowboys called five screens to a player lined up as an outside wide receiver against the Tampa Bay Buccaneers.

Three of these, one where running back Tony Pollard motioned into the position from across the formation and two to wide receiver Michael Gallup with either soft coverage or tight end Blake Jarwin in the slot lead blocking, gained nine yards on average. The remaining two averaged a meager 2.5 yards.

Click here for more PFF tools:

Rankings & Projections | WR/CB Matchup Chart | NFL & NCAA Betting Dashboards | NFL Player Props tool | NFL & NCAA Power Rankings

This disparity in outcomes, my personal hatred of screens to outside wide receivers and conversations with Football Outsiders and Bleacher Report contributor Derrik Klassen led me to ask a simple question: Are screens to outside wide receivers less inefficient than other types of screens?

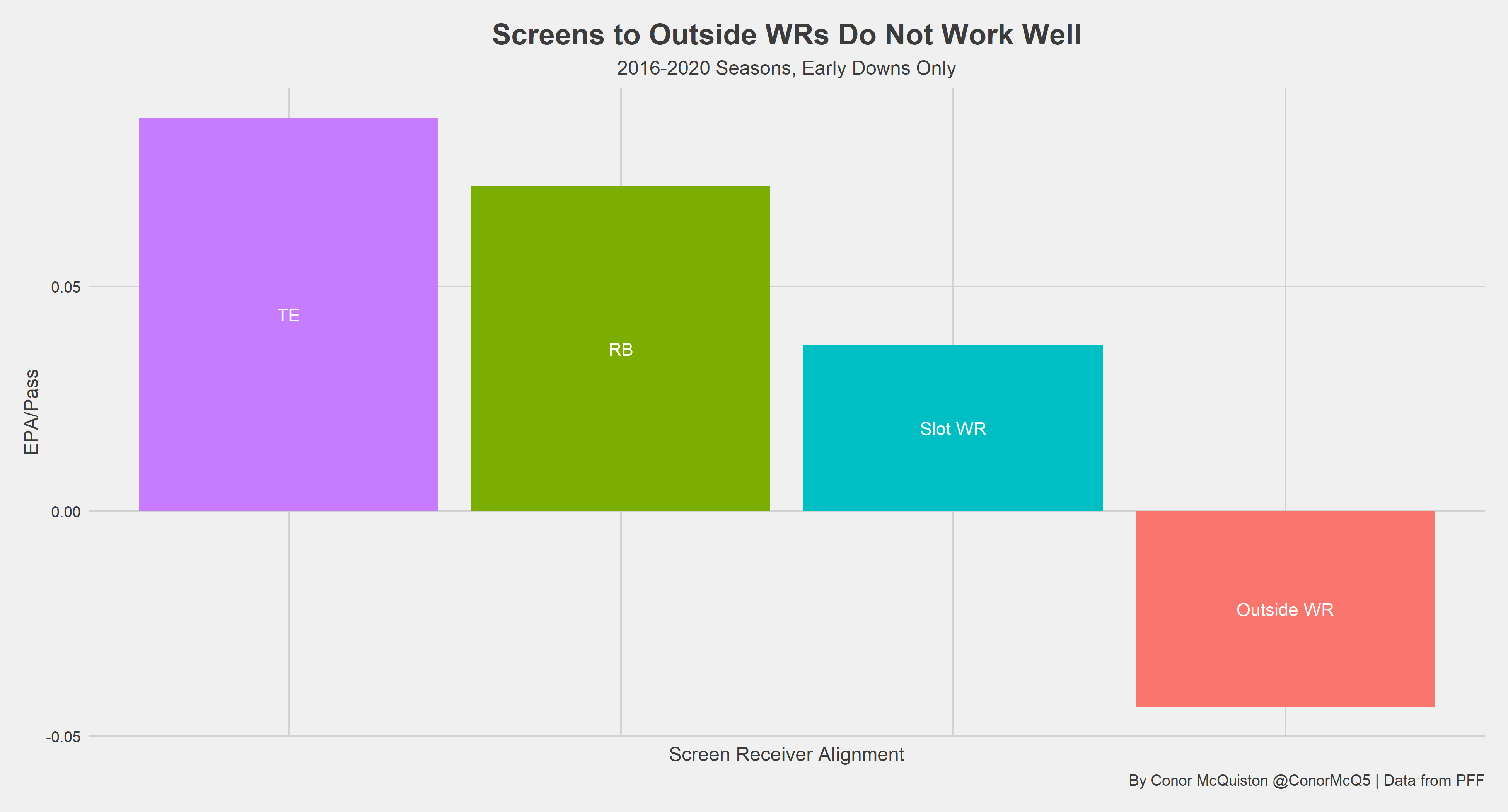

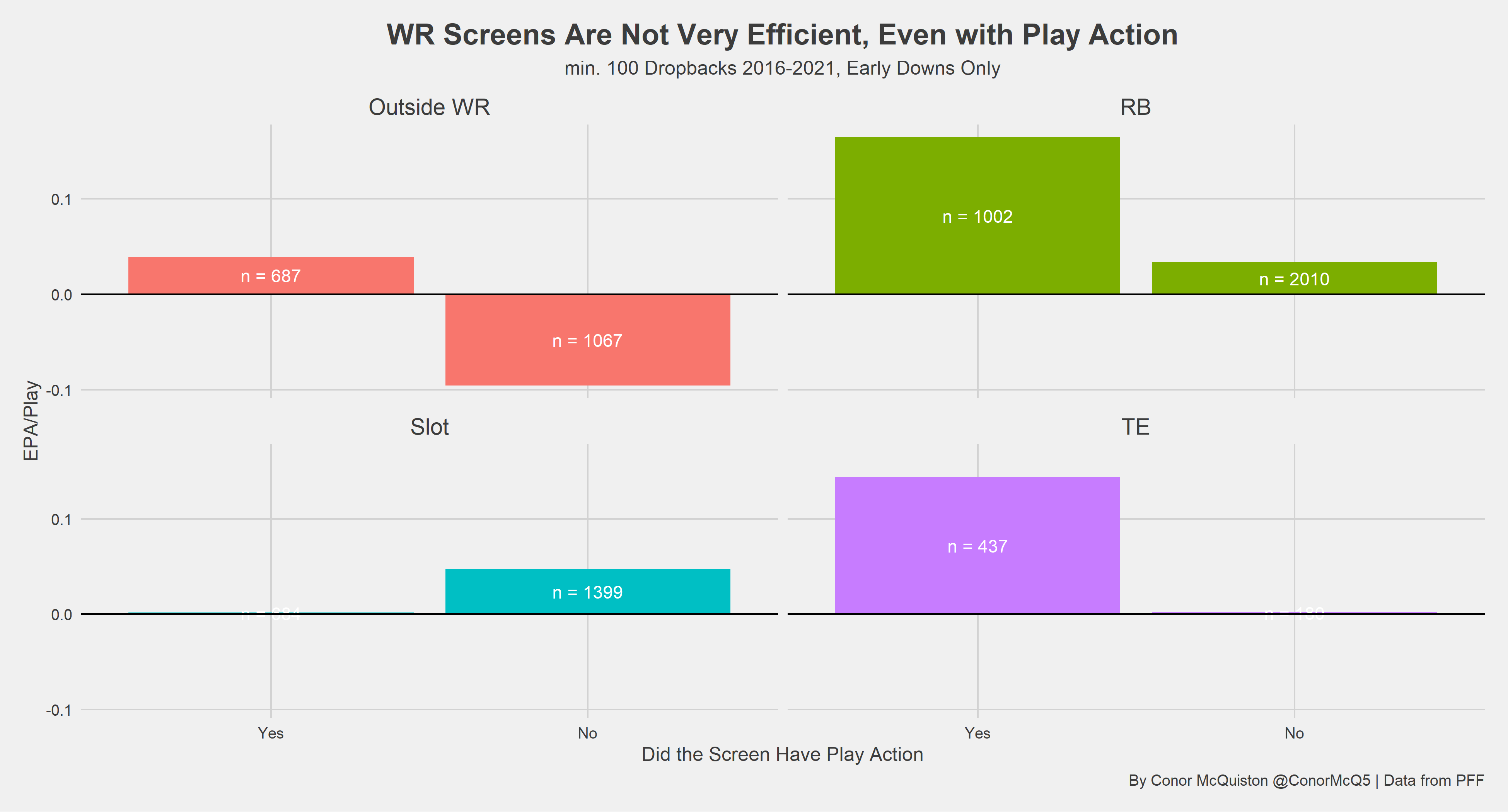

For our purposes, we will be excluding third downs from evaluating different screens so that we don’t have to worry about concession screens in third-and-long situations. With those plays excluded, the very simple answer to our question is “yes.” Screens to players who are aligned as the most outside wide receiver to a side on a given play (in football jargon, the No. 1 receiver on either side) are notably inefficient compared to other screens.

This ordering has a very simple explanation: Screens to outside receivers likely have at most two blockers in front of them — oftentimes wideouts who as of late are not strong run blockers. Tight end and running back screens are primarily behind several offensive linemen paving the way, and slot screens are split between heading back toward the ball, where they are behind better blockers, and bubble screens, where they have the same issue as the outside wide receivers.

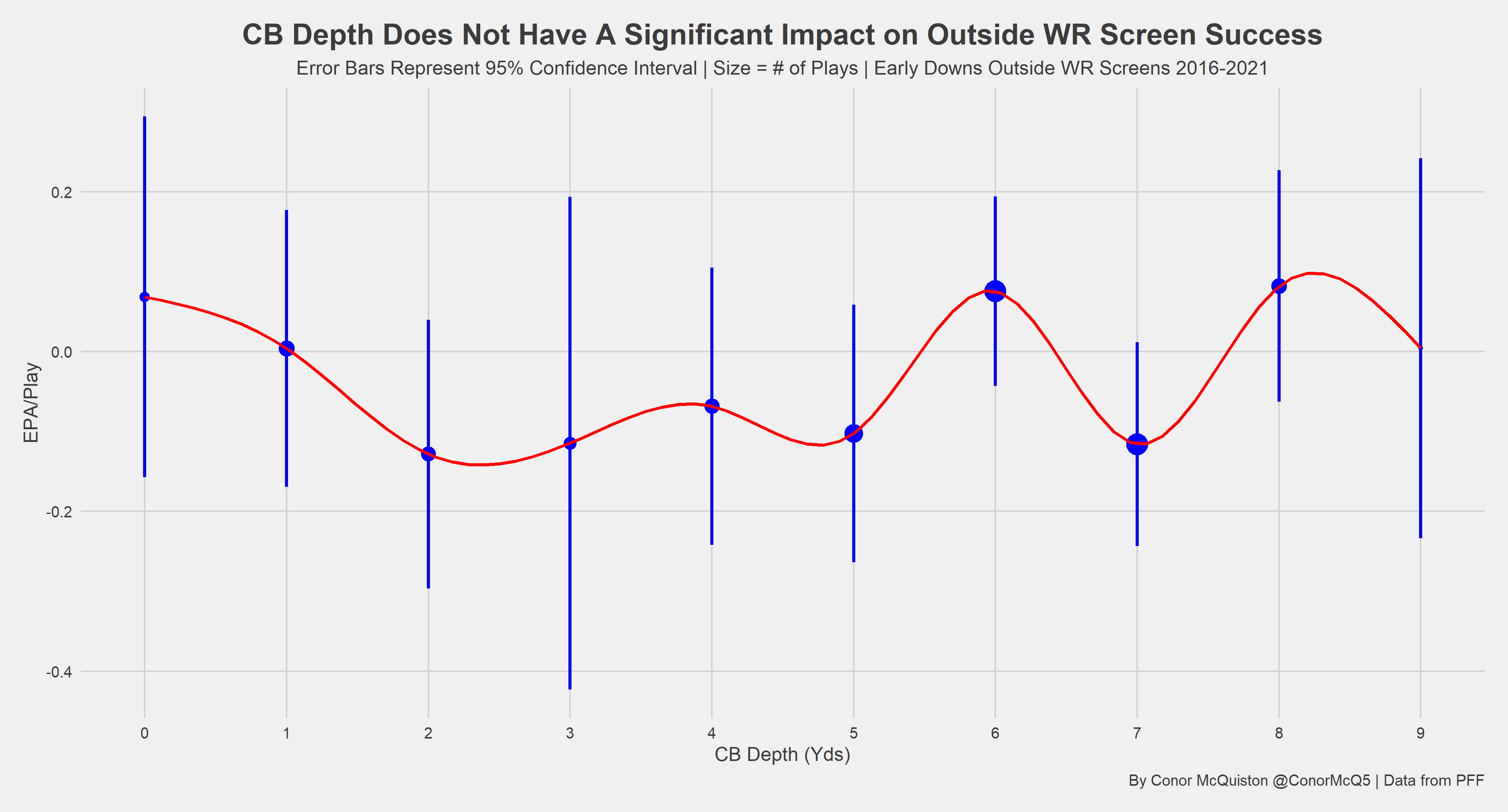

But maybe we’re missing the forest for the trees — maybe the success of a screen to an outside wide receiver is mostly a function of the defending cornerback’s depth pre-snap.

As it turns out, when we factor in uncertainty, we cannot say that the cornerback's depth pre-snap has an effect on the success of an outside wide receiver screen. In other words, on average, we cannot say that a screen ran against a cornerback who is seven yards off the ball will have more success than a screen ran against a cornerback who is two yards off the ball on average.

The on-field explanation for this is simple: the best athletes in the world can click and close on screens fast enough that their pre-snap alignment doesn’t make a significant difference on average. This is strong evidence that outside wide receiver screens are ineffectual, regardless of pre-snap alignment.

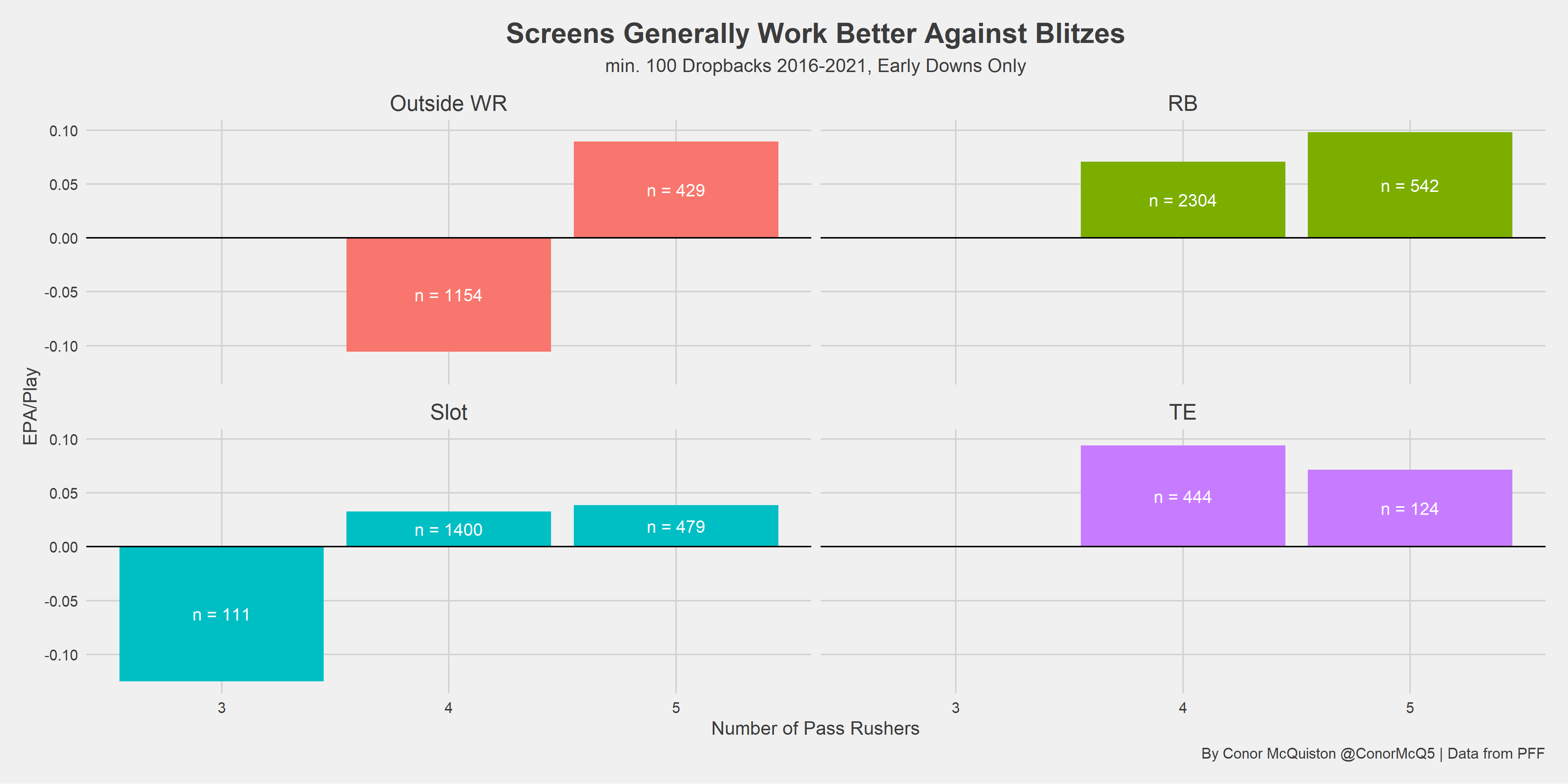

This doesn’t fully answer our question, however. It could well be the case that there are specific situations where outside wide receiver screens are actually the most efficient but are still overall the least efficient. They can act as hot reads to counter a blitz — a case where they could be particularly effective.

A quick aside: Throughout this article, tight end screens will generally be the most efficient screen type. This is partially because they have similar advantages to running back screens, but there is significant selection bias going on. Since 2016, the Kansas City Chiefs have called 11.7% of the NFL’s early-down tight end screens. This means that while tight end screens as a group are still efficient, they are likely inflated by the best receiving tight end in football, Travis Kelce, individually accounting for about one of every eight of its targets.

We see evidence for the hot read theory in the data, particularly in comparison to screens to slot players where outside wide receiver screens are roughly twice as effective when the defense brings an extra pass-rusher. This is still less effective than running back screens, but since the use case for outside receiver screens is different than running back screens — because they can be hot reads — this is fine. Unfortunately, despite their apparent utility when defenses bring a single blitzer, they are still wildly ineffective against a standard four-man rush.

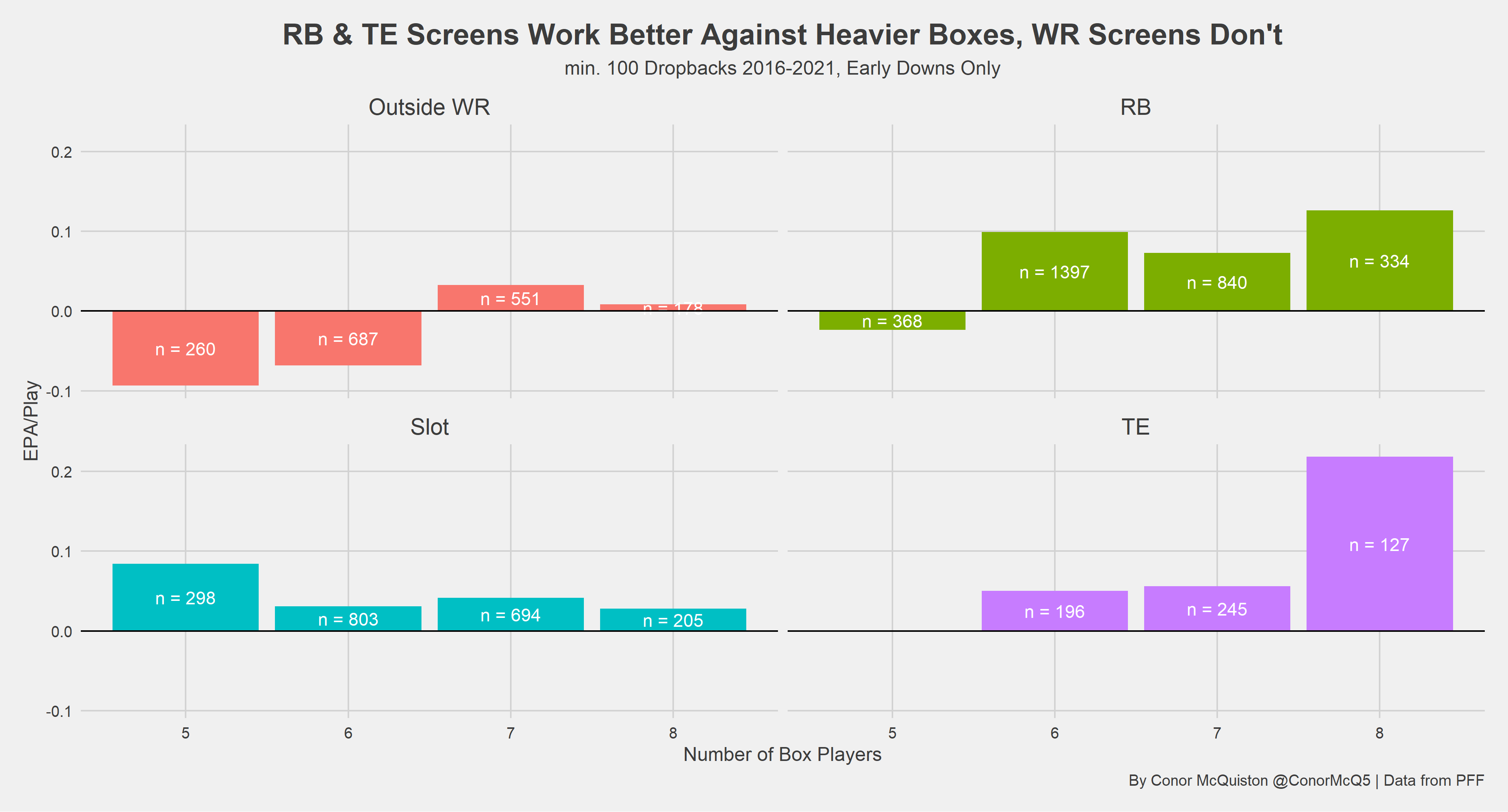

We now have evidence that outside wide receiver screens, and screens in general, are effective counters to blitzes. We also know that passes are generally more successful against heavier boxes, and since outside wideouts typically line up far from the tackle box, we may expect that those screens are particularly effective when facing heavy boxes.

The actual relationship between box count and screen success is much murkier than expected. The effectiveness of screens to slot receivers, running backs and tight ends is relatively constant across box counts. Tight end screens’ particular success against eight-man boxes is mostly the result of the Kansas City Chiefs, Dallas Cowboys, Tennessee Titans and San Francisco 49ers accounting for 51% of the positive expected points added (EPA) on those plays. Even for outside wide receivers, there is a negligible difference in efficiency between seven- and eight-man boxes, as well as five- and six-man boxes.

This explanation probably once again boils down to the number of blockers the screen target has in front of them. Regardless of box numbers, tight end, running back and slot screens tend to have advantageous blocking numbers since they're occurring closer to the middle of the field, resulting in better outcomes.

Similarly for outside receivers, lighter boxes mean they are more likely to have more defenders across from them than their blockers can account for, leading to worse outcomes. This gets rectified with heavier boxes, but since their blockers are generally worse, they don’t get the same positive outcomes.

Perhaps the key to unlocking the potential of outside wide receiving blocking is coupling them with play action. We know play-action passes are extremely efficient, so perhaps that will give such screens a much-needed boost.

Play action immensely boosts the efficiency of running back and tight end screens. This makes sense because offenses are able to effectively make their run game look similar to those particular screens, thus making that play action effective at drawing in the defense.

Outside wide receiver screens are more effective when attached to a play-action fake, but this positive effect is muted since the corners covering them oftentimes have only a small role in the run fit. Therefore, even if the cornerback across from them bites on the run fake, the results aren’t catastrophic — especially since they can typically fight through the weaker slot receiver's blocking.

The aberration of ineffectual slot receiver screens with a play action is likely a result of most slot receiver screens with play action being bubble screens, which rely upon wide receiver blocking for their success. Thus, such screens have the same pitfalls as typical outside receiver screens.

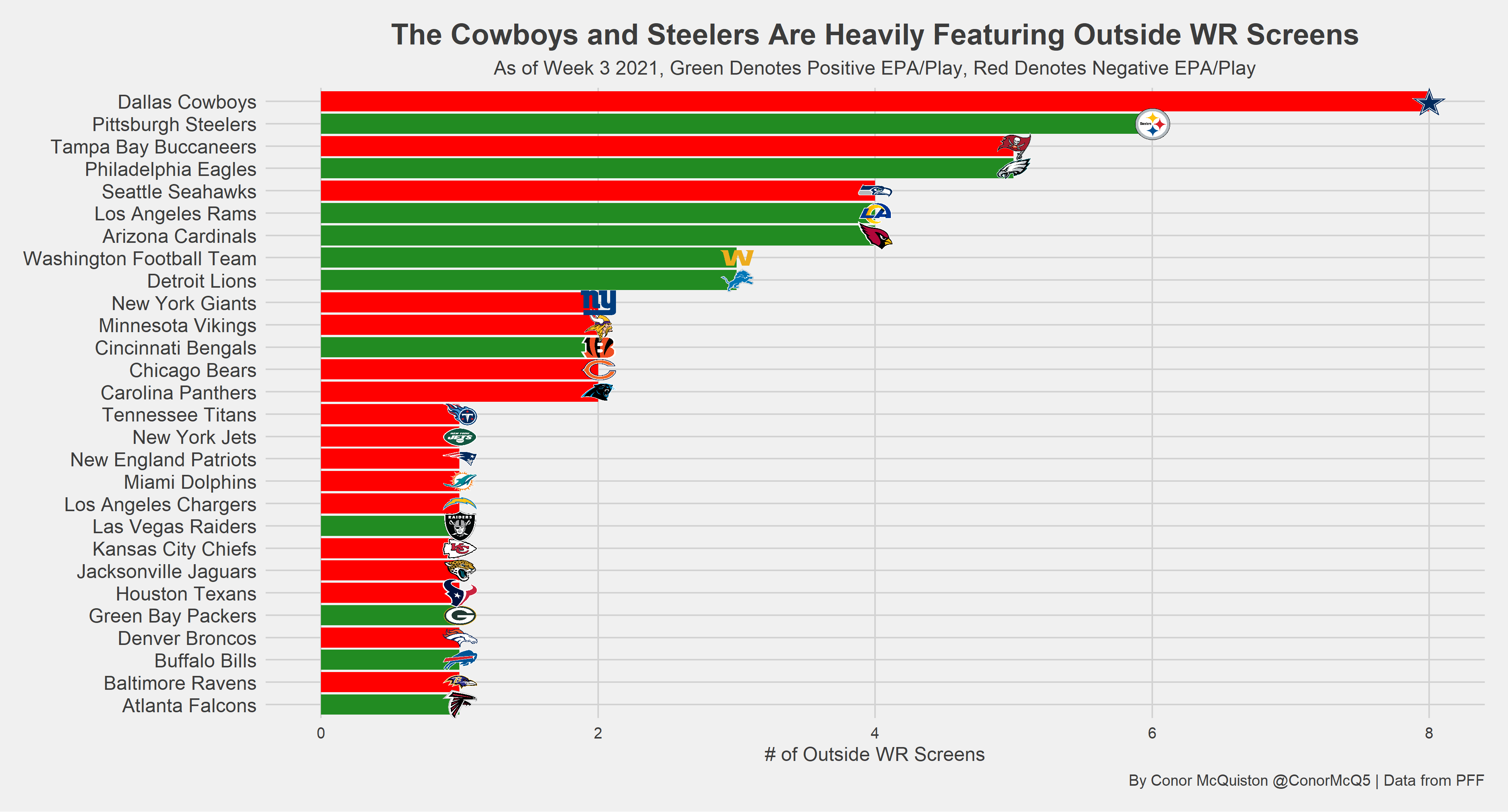

So, we’ve learned that outside wide receiver screens are particularly efficient on early downs when they are being used to counter a single blitzer, likely as a quarterback's hot read, and are generally less efficient otherwise. Now, which teams have watsed the most value thus far in 2021 by throwing these outside receiver screens?

We're only in Week 3, though, so these are extremely small samples. Still, it appears the Cowboys and Pittsburgh Steelers are particularly keen on throwing screens to outside wideouts, with the Philadelphia Eagles and Buccaneers not far behind. This is not a surprising strategy for any of these teams, considering the talented receiving corps in Dallas and Tampa Bay, and the limited quarterbacks taking the field for Pittsburgh and Philadelphia. The latter two currently boast positive EPA per play marks on screens that target outside wide receivers, which may suggest an argument that they are uniquely effective in executing these plays and thus are an exception to the rule.

Most of the positive EPA on these plays for Pittsburgh came from three passes against the Buffalo Bills, and the same is true for Philadelphia when the team played against the Atlanta Falcons’ porous defense. After contextualizing that production, and acknowledging that the more talented Dallas and Tampa Bay rooms are inefficient running these screens in aggregate, we can safely assert that these teams are throwing away value by tossing more outside wide receiver screens.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.