It’s been this way for decades, but it’s truer now than it’s ever been: the National Football League is a quarterback league. Whether it’s using traditional statistics like yards per pass attempt, something more advanced like expected points in the passing game, or our own PFF grades, nothing moves the needle in terms of winning games more than having plus play at the quarterback position.

Likely in reaction to this truth, teams have been more than eager to use the tools they have at their disposal to acquire talent at the position: high draft capital and big contracts. Of the 32 NFL teams, 20 are starting quarterbacks that were selected in the first round by that team, while another two (Oakland and Cincinnati) are starting quarterbacks they themselves selected in the early second round. Tom Brady, Russell Wilson, and (to a far lesser extent) Dak Prescott are exceptions to the rule, having been drafted later by their current team, while Jimmy Garoppolo and Kirk Cousins found a second home (furnished expensively) after outperforming their draft position for their original team.

The winner’s curse, as it were, is that once a quarterback outperforms what is, after the 2011 CBA agreement, an extremely modest rookie deal, there is significant pressure for him to “reset the market” at the position. As a result, the NFL’s highest-paid quarterback (measured by either total contract or per-year) have often been players like Joe Flacco, Matthew Stafford, Derek Carr, Garopollo and Cousins – signal callers that, while good players, are not true difference makers at the position. Furthermore, the six highest-paid quarterbacks last season played for teams that, for a number of reasons, did not make the playoffs, calling into question the efficacy of paying top-dollar for a quarterback.

So, the question after last week’s four-year, $140-million extension for Russell Wilson with the Seattle Seahawks, particularly since Seattle has only four draft picks in this week’s draft, and substantial needs across their roster, is: Did the front office do the right thing?

Wilson is truly an elite player at the position, generating the sixth-most wins above replacement since being drafted in the third round of the 2012 NFL draft, behind only Brady, Drew Brees, Matt Ryan, Aaron Rodgers, and Ben Roethlisberger among quarterbacks in that span. So, unlike players like Flacco, Stafford, Carr, and Cousins, one can make a case for Wilson to be, at a given time, the highest-paid player at the position. That said, being a member of the list above does not guarantee team success; Ryan and Brees have each missed the playoffs in three of the last five years, Aaron Rodgers’ Green Bay Packers have had a losing record the last two seasons, and Big Ben’s Steelers missed the playoffs in 2018. The only quarterback in that group to win a Super Bowl since Russell Wilson in 2013 is Tom Brady, whose salary has been a modest percentage of the Patriots payroll for a while now.

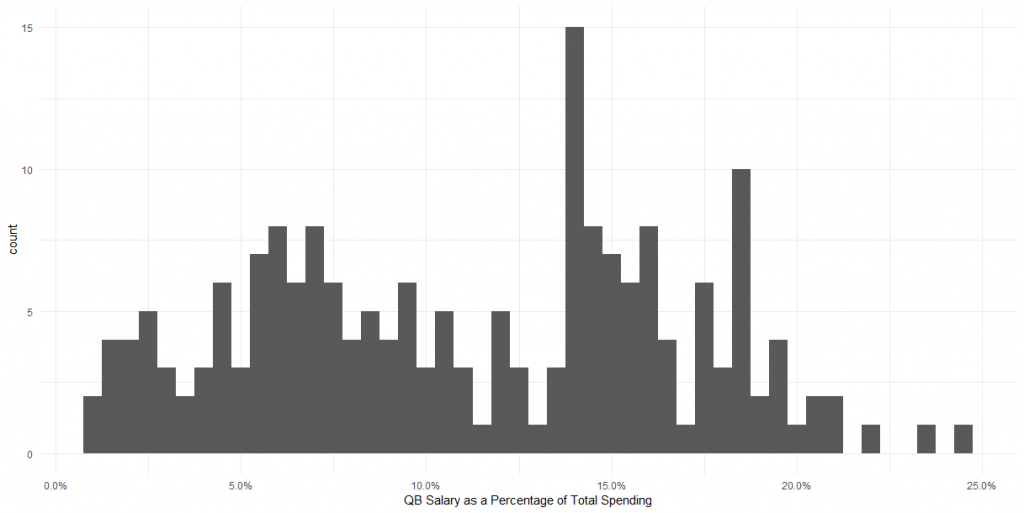

To study this further, I grabbed salary data from our friends at OverTheCap.com (who do terrific work), and I used their measure of total spending by position group from 2013 – 2018 (where their data is available). As expected, there’s a bimodal distribution when looking at the quarterback position’s percentage of the total team spending – some teams having young quarterbacks on modest rookie deals (plus relatively inexpensive backups), while others have veteran quarterbacks on market-level deals.

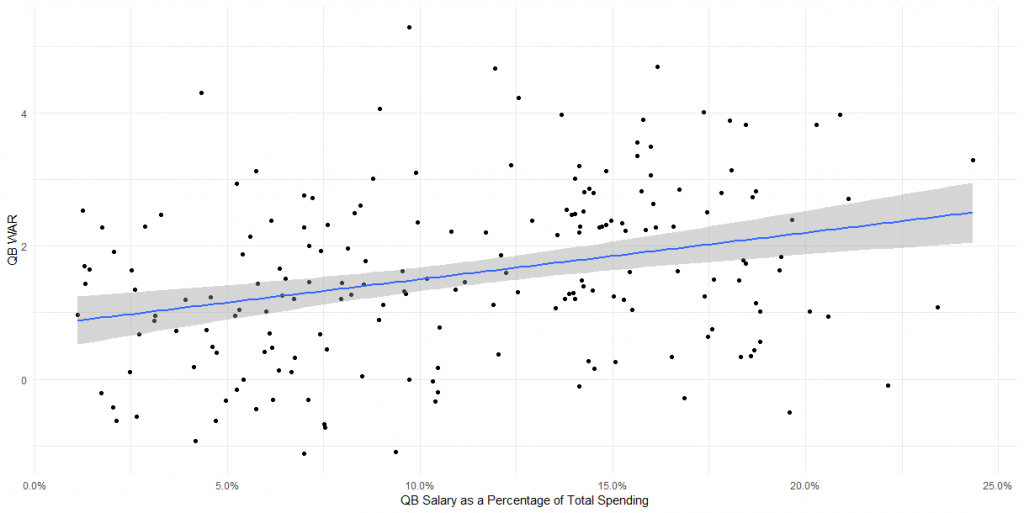

Does paying a quarterback more get you a better quarterback?

A natural question is whether or not teams are getting plus performance out of their quarterback as a result of paying them a bigger share of their payroll. Using PFF’s wins above replacement model (WAR, the full methodology of which will be released within the coming weeks) we measured the number of wins a team should have had in a given season by adding up their WAR (and adding three additional wins as the baseline). I then took the quarterback’s WAR, along with that WAR’s percentage of its team’s implied wins, and found that both metrics had a statistically significant relationship with the quarterback’s percentage of payroll. However, the relationships in both cases are pretty weak (r-squared equal to 0.092 and 0.108, respectively), showing that, while higher salaries do on average lead to better play at the quarterback position, they do not guarantee it.

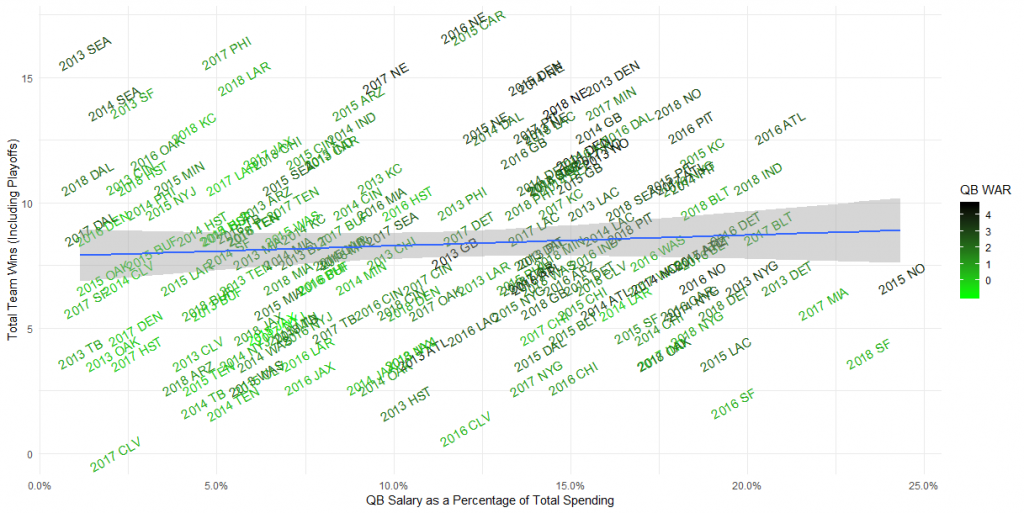

Does paying a quarterback more lead to more wins?

However, the point of the discussion is whether paying quarterbacks top dollar leaves too little in the way of additional spending to compete – due to a lack of talent on the rest of the roster. To test this hypothesis, we looked at total team wins (including playoffs) versus the percentage of team spending allocated to the quarterback, and we found no statistically significant relationship. This has been noted by a few authors, but to add some context to the discussion, we also displayed the WAR for each team’s leading quarterback (in terms of snaps) heading into that season as a measure of how “elite” the signal caller of that team was – as we know that there are plenty of teams that pay non-elite quarterbacks significant money. Darker shades of green imply better quarterbacks entering the year (WAR entering the year isn’t a perfect measure. See Patrick Mahomes, who had basically no WAR heading into 2018). Data points above the straight line are teams performing better than expected and those below the line are worse.

Notice that the two clusters of teams remain in this graph, each a collection of points move down and to the right as QB salary increases. The cluster on the left is mostly comprised of teams with quarterbacks on a rookie deal, with the darker shades of green being teams like rookie-contract Russell Wilson’s Seahawks and the Dak Prescott Cowboys. Other notable teams in that group are the Carson Wentz/Nick Foles Eagles, the Deshaun Watson Texans, the Jared Goff Rams, and the Teddy Bridgewater Vikings, to name a few.

The second cluster includes teams paying quarterbacks a hefty sum, and while there are plenty of teams that are generating high win totals, the vast majority are doing so with high-WAR quarterbacks at, or around, 15% of total team spending. Only the 2016 Falcons and the 2018 Colts performed better than expected with quarterbacks earning more than 20% of team spending.

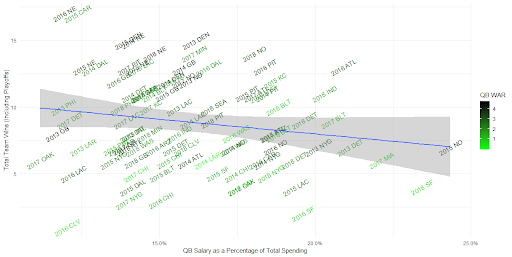

What we see in the graph above can also be inferred mathematically, as a linear model with a quarterback’s average WAR in his previous three seasons yields an r-squared of 0.149 with total team wins, which increases to 0.166 if one adds the percentage of payroll taken up by the quarterback position. The latter variable becomes a statistically significant and negative predictor (at the p = 0.10 level) once the strength of the team’s quarterback position is factored into the model. This instance of Simpson’s paradox can be seen when one only looks at the graph with quarterback proportion of team spending above 11%, where the trend line is now downward sloping:

The downward-sloping curve on the other (left) side of the graph is due in large part to the fact that lower-paid veterans are likely not as good as rookies good enough to play significant snaps, but often make a tad more (for example, Ryan Fitzpatrick will make more than Patrick Mahomes, Dak Prescott, Deshaun Watson and Lamar Jackson in 2019).

Conclusion

Scarcity is real in the NFL; every dollar that is spent on one player cannot be spent on another, and while the quarterback is the most important position, there are even diminishing returns to paying them too much money. That said, not every quarterback will be as gracious as Tom Brady, who consistently takes less than he’s worth to help the Patriots build a winning team (even that dynamic appears to be abating in 2019, with Brady taking a bigger share of New England’s cap than before).

Some players, like Russell Wilson, will command top dollar, and the real question is whether or not they will deserve it. Wilson likely does. He’s averaged over 2.5 WAR in his first seven seasons. Teams with quarterbacks earning 11% or more of their team’s spending going into the season with quarterbacks averaging 2.2 WAR the previous three seasons win 10 or more games (including playoffs) roughly 60% of the time. Teams without such quarterbacks do so just under 30% of the time. These cutoffs are arbitrary, but make the point – the only time you should pay a quarterback top dollar is A.) If he's in the elite group that contains Brady, Brees, Ryan, Rodgers, Roethlisberger, Rivers, Luck, and Wilson or B.) If he's projected into this top group in the future.

Along that vein, teams need to be able to project their rookie-deal quarterback forward in a way that can differentiate between a good quarterback and a great one. This is not a trivial task – since confounding variables like supporting cast and defense will take different values when a signal caller is on his rookie deal than when he is paid like a top-flight starter. Things like Pro Football Focus grades and quarterback clusters – that differentiate between process and results and go a long way toward differentiating credit in the passing game can help us in this regard, as can the context-adjusted projection systems we’ve discussed for college players in the lead up to the draft. Looking at stable subsets of data like clean pockets will also help in determining if a quarterback is a flash in the pan or a real superstar in the making. If he’s a true superstar, pay him. If not, move on… even if he’s good.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.