The Cleveland Browns recently signed running back Nick Chubb to a three-year, $36.6 million extension despite recent running back extensions not working out. The Los Angeles Rams gave Todd Gurley a four-year, $57.7 million dollar extension but had to cut him early into the deal. A similar story played out when the Arizona Cardinals signed David Johnson to a three-year, $39 million deal and then traded him as part of a salary cap dump shortly afterward.

Subscribe to

The Browns' deal with Chubb might be different. For one, he’s been one of the best running backs in the NFL, averaging a league-leading 0.89 rushing yards over what an average running back would have done in the same situation — the league's best mark since 2018. More importantly, he doesn’t have the wear and tear that Gurley and Johnson did when they signed their extensions. When Gurley was slated to start his extension, he had 1,042 career rushes in the NFL, while Chubb has only has 693. Johnson had a lengthy history of injuries in the NFL, including thigh, knee, wrist and ankle issues, while Chubb has only been injured once since college.

There's a lot of surface-level talk about running back workloads — whether players at the position tend to regress around a certain age or how one year's workload affects future seasons. Some of these hold weight when looking at the data, while others don’t.

To evaluate these facts and fictions, we can use Rushing Yards Over Expected (RYOE). RYOE adjusts the rushing yards a running back picks up by accounting for situation. For example, it’s much harder to gain 2 yards on a first-and-goal from the opponent’s 5-yard line than it is on a third-and-15 from the middle of the field.

Now that we have a baseline for evaluating running backs, we can dive into the facts and fictions of running back workload regression.

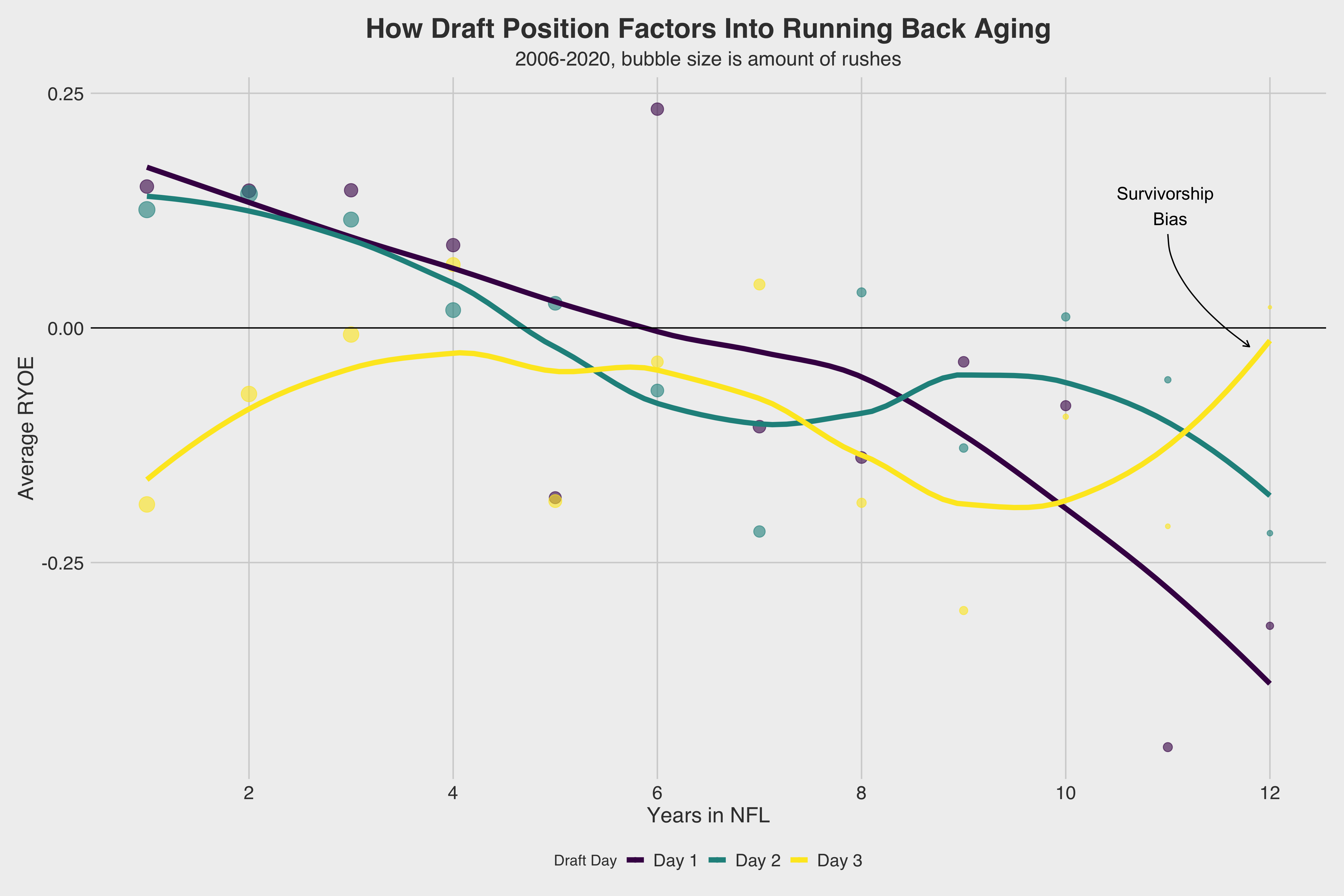

Fact: Running Backs Drop Off after Their Rookie Contracts

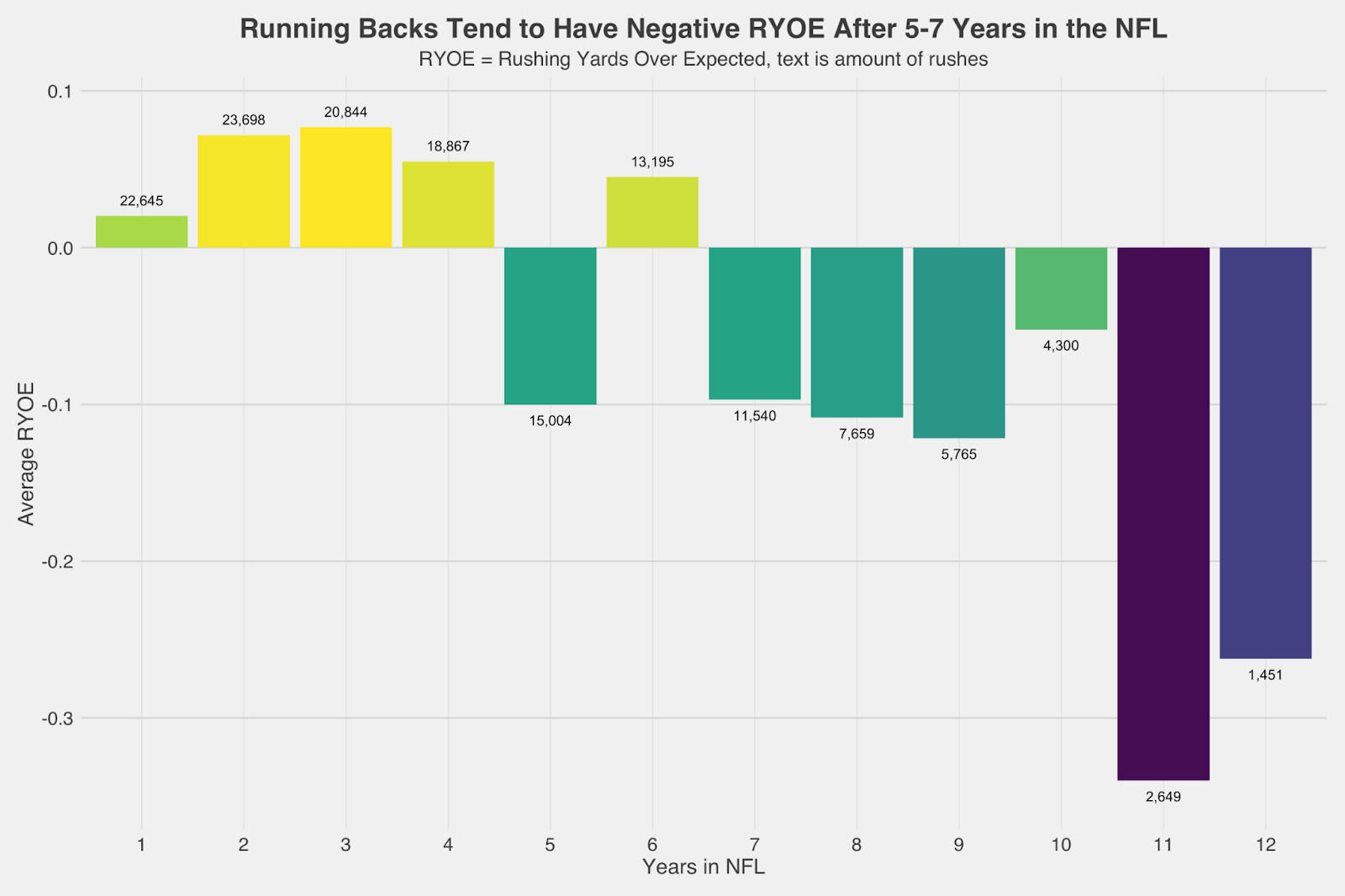

In the NFL, rookie contracts last for four years (with a fifth-year option for first-round selections). Running backs on their rookie deals usually see some success: They rush for an average of 0.07 rushing yards over expected, which might not seem like much but is better than what happens after that.

When looking at the average RYOE for each year spent in the NFL, Year 5 onward seems to be when running backs start to accumulate negative rushes. Except for the slight positive blip in Year 6, running backs average -0.1 RYOE per year during Years 5-10, and it becomes drastic in Years 11 and 12.

However, there is some strong survivorship bias in play here. An example of the concept: People often cite Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg as college dropouts who became billionaires but fail to consider all the other college dropouts who didn’t reach that level of success. In the football world, this can mean all the running backs who didn’t make it to Year 5 onward were probably not that good. That means only efficient running backs are making it to the second contract; considering this, the drop-off suddenly seems more drastic.

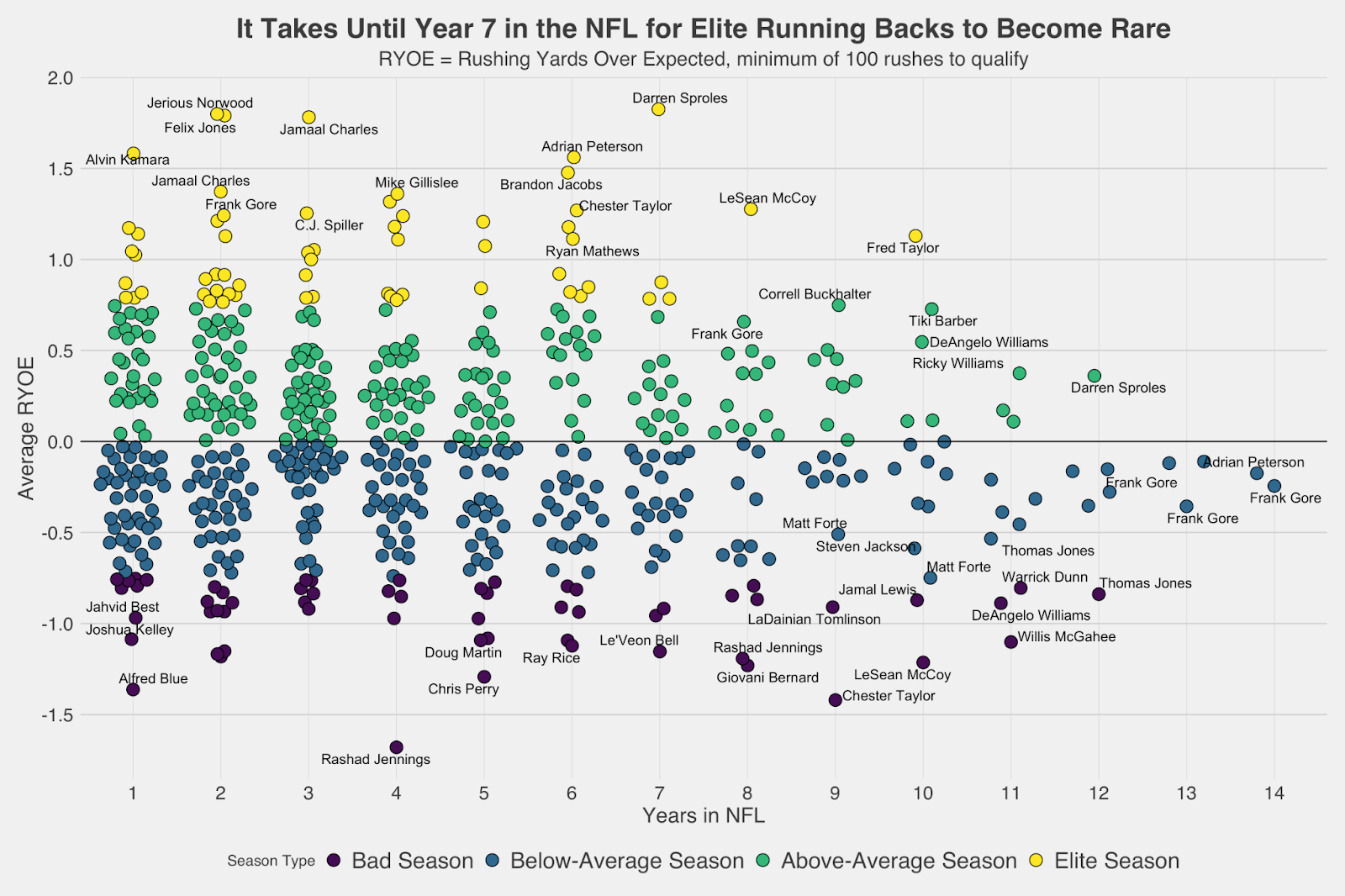

Usually only good running backs make it to Year 5, and those are the running backs that are earning negative RYOE. We can see the story play out when looking at specific running backs and binning by elite, above-average, below-average and bad seasons.

There are a plentiful elite running backs seasons during Years 1-7, highlighted by Alvin Kamara’s rookie season, Jamaal Charles’ Years 2-3 and Aaron Jones’ 2020 season in Year 5. However, these performances taper off as a running back's career moves on. LeSean McCoy had an elite season in Year 8 with a +1.21 RYOE/rush, only to have a bad season in Year 10 with a -1.19 RYOE/rush. A 2.4 rushing yard over expected decrease demonstrates how quickly running backs can fall off.

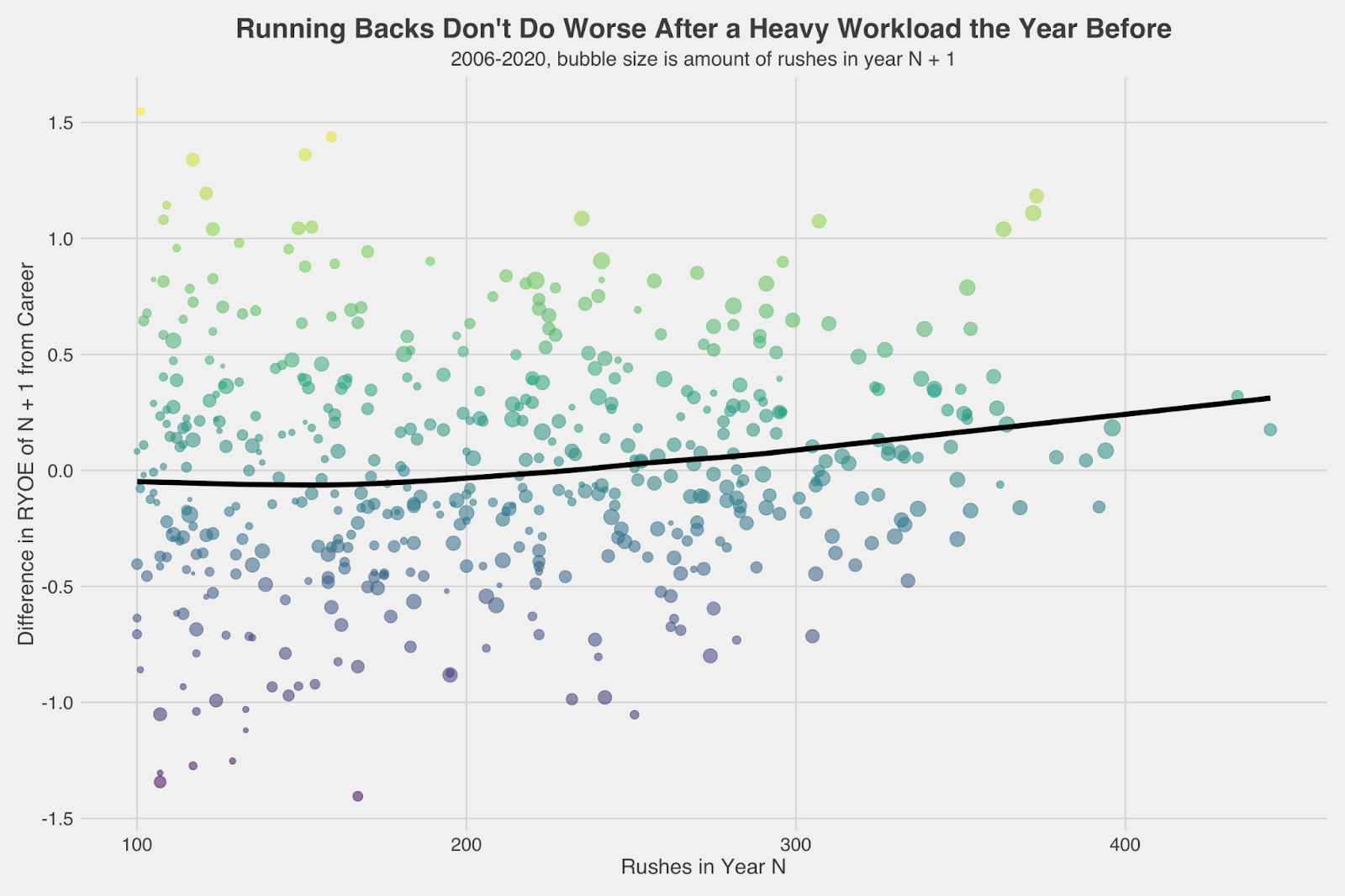

Fiction: Running Backs Burn Out After Receiving a Heavy Workload the Year Before

The NFL offseason is longer than most leagues, as it spans nine months for most teams, but this time off is needed for players to rest and recover from the damage of the previous season. Analysts have made the argument that a 300-plus carry season for a running back can wear the player out to the point he is still burnt out by the time a new season rolls around. This doesn’t seem to be the case.

There is no correlation between a running back's workload one year and the change in the RYOE from their career average the following year. The huge workload is not affecting them relative to how they usually perform. This is especially true when looking at specific case studies.

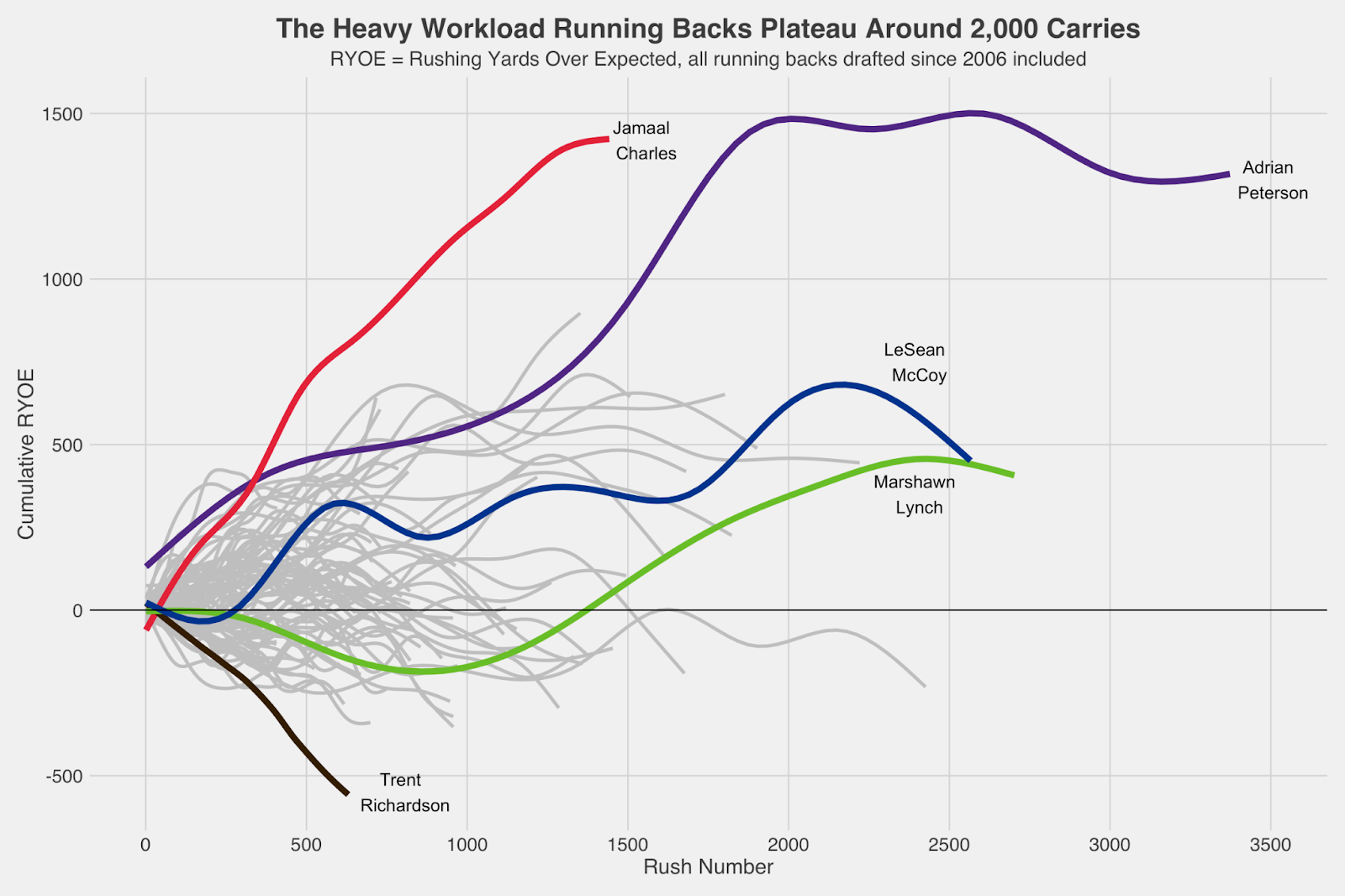

Adrian Peterson, the running back with the second-most cumulative RYOE in the PFF Era (2006-20), ran the ball an average of 323 times his first six years in the NFL. Despite having such a strong workload every year, he was able to build up over 1,000 total rushing yards over expected and almost reached 1,500 before he started to plateau. Both LeSean McCoy and Marshawn Lynch have similar stories, as they were receiving heavy workloads and rising in cumulative RYOE but weren’t able to keep it up after the 2,000-carry limit.

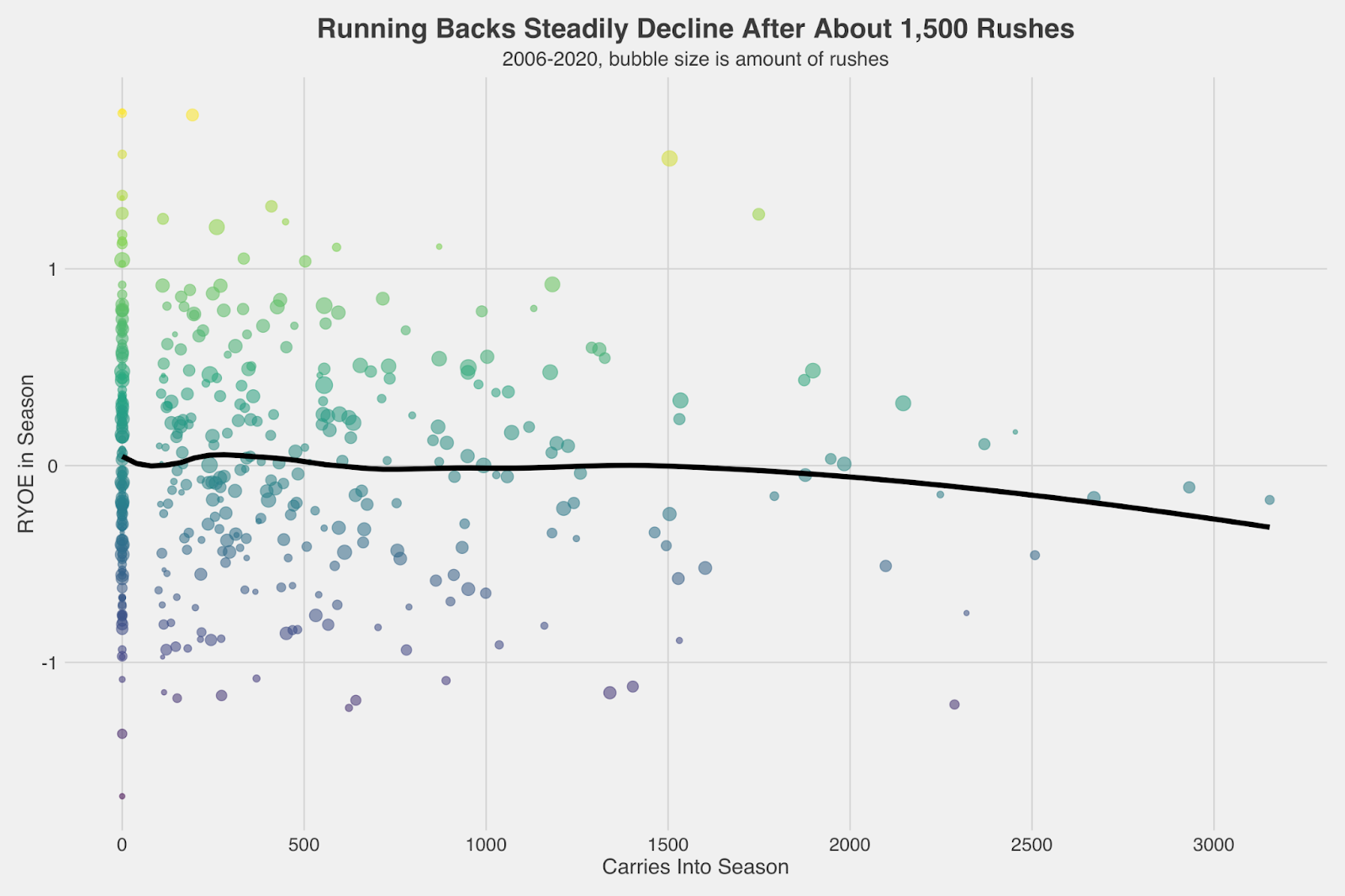

Fact: For All Types of Running Backs, There is a Carry Limit Where We Can Predict a Negative RYOE

We looked previously at elite running backs having less success after hitting that 2,000-carry threshold. The plot above shows all types of running backs and finds that 1,500 carries heading into a season usually means a dropoff is coming. In the PFF era, there have been 27 seasons where a running back had at least 1,500 carries going into the season — only seven of those seasons resulted in positive RYOE. The trendline is clear once a running backs gets that many carries — he usually show signs of regressing.

This trend seems to be running back specific — it doesn’t appear to follow other positions. We just saw Aaron Rodgers win an MVP at age 36 by leading the most efficient passing attack in the NFL. At age 32, Cole Beasley was one of the best slot receivers in the NFL and even received an all-pro vote for his performance. Conversely, by the time running backs hit 27, they are usually past the prime of their careers.

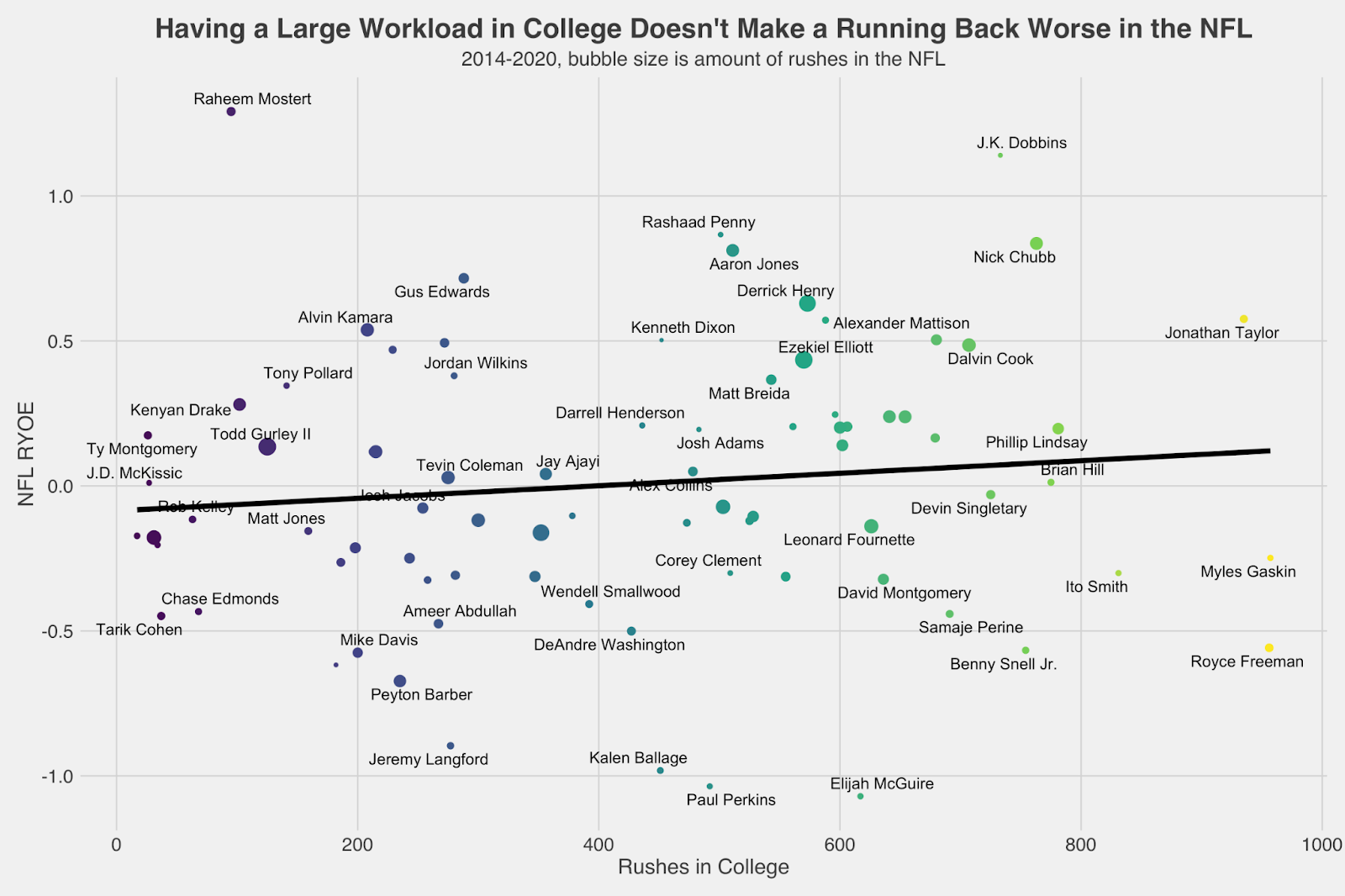

Fiction: A Heavy College Workload Means the Running Back Won’t Do as Well in the NFL

Draft analysts often like to reference the amount of carries a running back received in college as a reason for why they should be drafted higher or lower. A running back who was a workhorse during their NCAA career has more doubts cast upon their future in the NFL, while a running back who saw a lighter workload is often labeled as “fresh.”

This doesn’t seem to be the case. Nick Chubb and Dalvin Cook both spent years as a focal point of their college offenses and have emerged as two of the best running backs in the NFL. There is little to no correlation between how many rushes a running back accumulates in college and their NFL performance. Tarik Cohen and Mike Davis being “more fresh” didn't lead to better performance in the NFL.

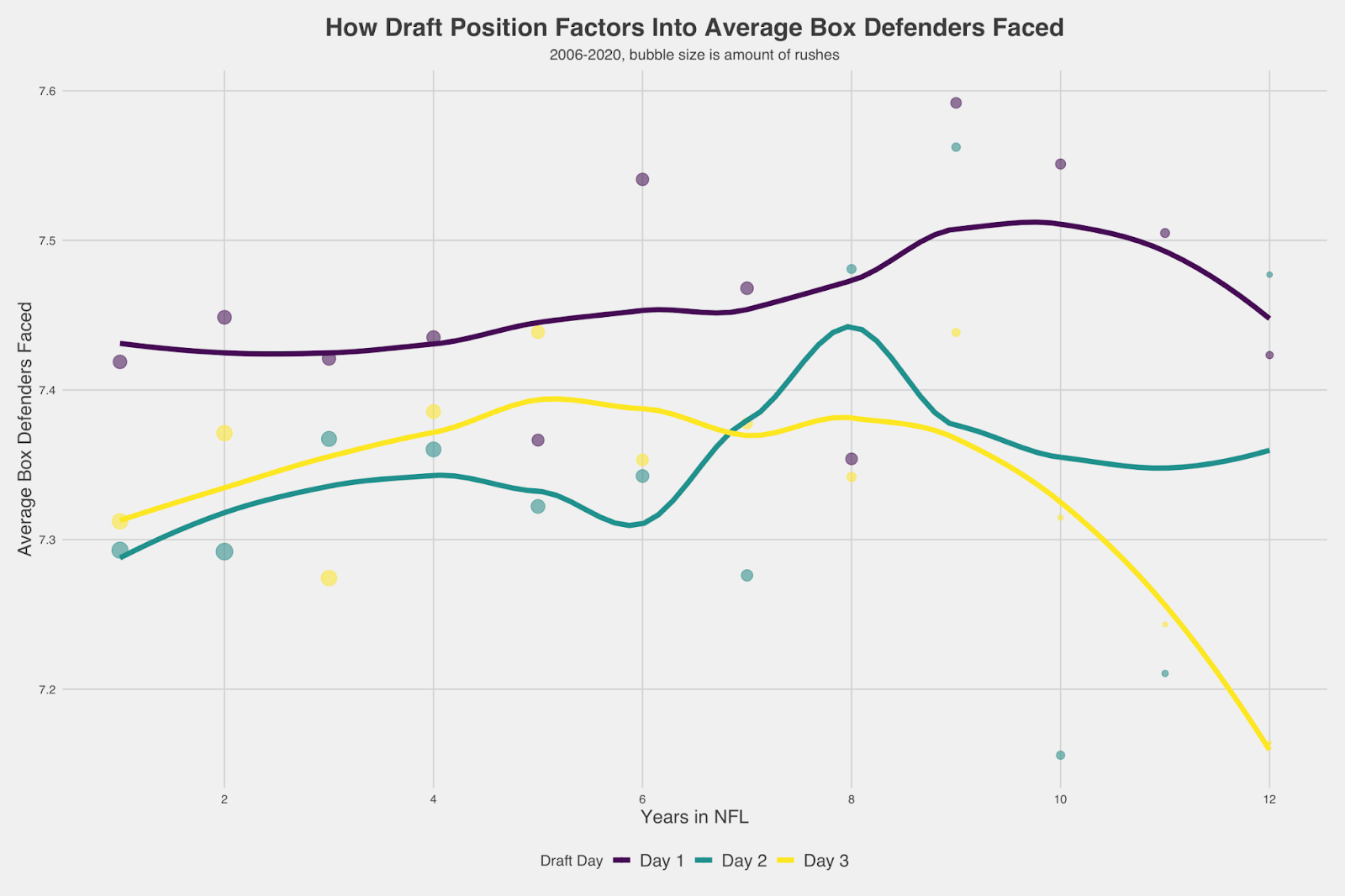

Fact: The Draft Position of a Running Back is More Important than the Actual Running Back Himself

PFF's Zach Drapkin looked into how a player’s draft position stays relevant throughout contract negotiations and how higher-drafted players often get more money despite similar performances.

An important variable in determining an expected rushing yards for each play is the amount of defenders in the box at the snap.

Running backs drafted on Day 1 (first round) see a much higher box count throughout their entire careers. Day 2 (Rounds 2-3) and Day 3 (Rounds 4-7) see lighter box counts when rushing. Even though drafting a running back in the first round usually isn't beneficial to an organization, having a highly drafted running back in your backfield can actually help your passing game. Defenses will stack the box more when threatened by a first-round running back, making it easier for the passing offense to succeed, as it’s easier to pass when there’s more defenders in the box.

These Day 1 running backs are put into tougher situations, so by averaging the same amount of yards per carry as Day 2 and Day 3 back, they are given a higher RYOE for the first couple years of their careers. We can see Day 1 and Day 2 backs are given more opportunities as their careers go along, reaching negative RYOE around Year 5, like previously discussed. Survivorship bias plays a strong role in running backs drafted in Rounds 4-7 because they have to fight to stay on rosters to get opportunities and actually “peak” toward the end of their career, as all the good Day 3 rushers survived.

Fiction: Adrian Peterson Should Have a Higher RYOE than Jamaal Charles Because Charles Didn’t Play as Long

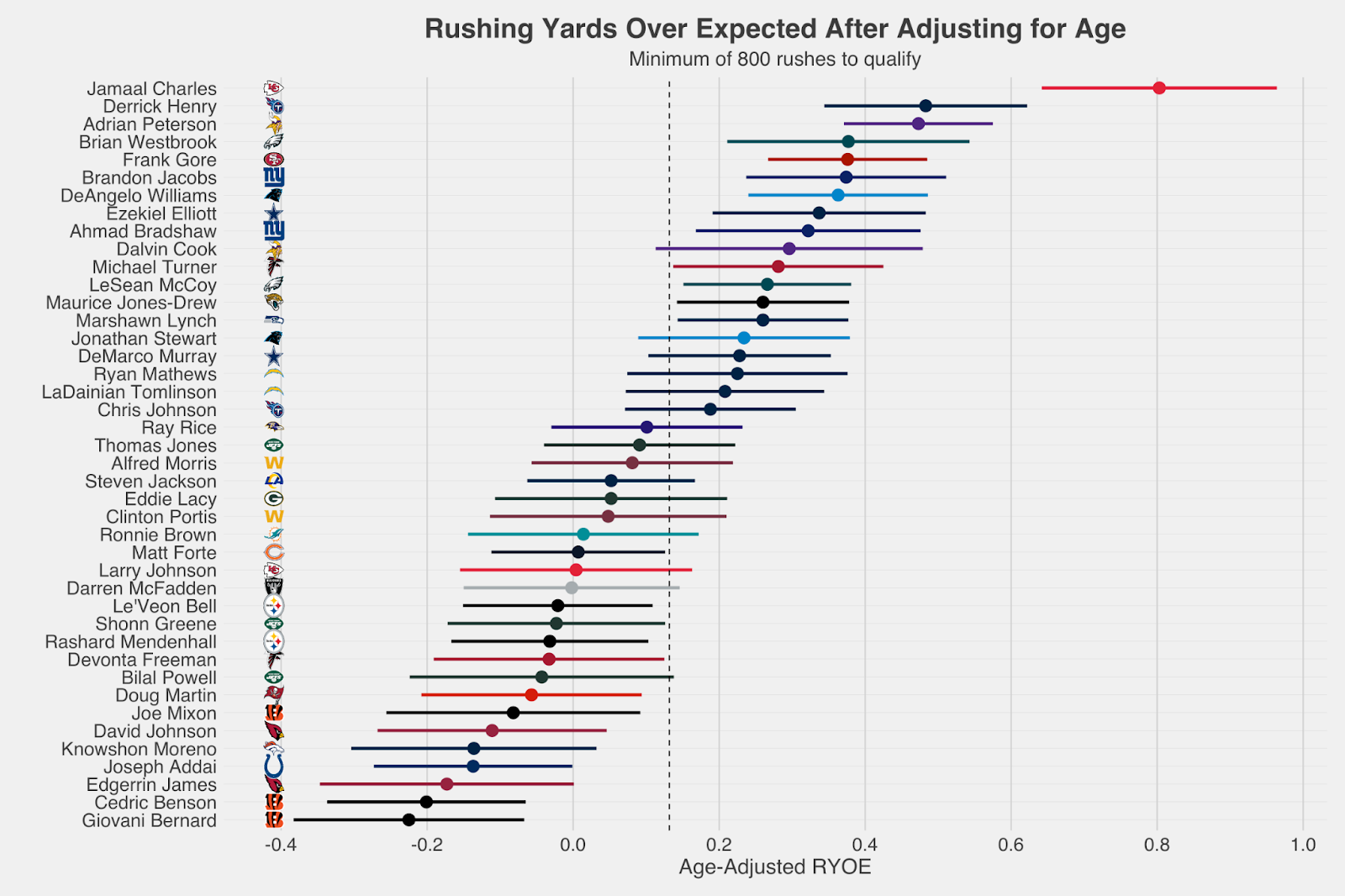

When posting all-time RYOE graphs on Twitter, a common response is that Adrian Peterson’s career RYOE would have been higher if it wasn’t for his longevity, while Charles retired during his prime. Using an effects model with the running back as the random effect and the amount of years spent in the NFL as the fixed effect, we can see how the average RYOE changes by age and apply that to an adjusted RYOE.

| Years in the NFL | Adjusted RYOE Based on Rusher Strength |

| 1 | +0.02 |

| 2 | +0.03 |

| 3 | -0.01 |

| 4 | -0.03 |

| 5 | -0.21 |

| 6 | -0.06 |

| 7 | -0.22 |

| 8 | -0.24 |

| 9 | -0.32 |

| 10 | -0.28 |

| 11 | -0.59 |

| 12 | -0.56 |

| 13 | -0.67 |

This is slightly different from the earlier bar graph showing average RYOE at each year spent in the NFL, because it attempts to adjust for the strength of the running back and just factor the years spent running in the league. It follows a similar pattern as the bar graph, as running backs fall off after Year 5 and severely regress starting in Year 11. However, even after adjusting for age, Jamaal Charles’ average RYOE still blows everyone away.

Charles had a 0.79 age-adjusted RYOE per rush — the ceilings of Derrick Henry and Adrian Peterson weren't close to his average. Marshawn Lynch and LeSean McCoy moved up from their normal RYOE as they rushed late into their careers, too.

To summarize: Running backs usually fall off once they hit 1,500 carries and have played five to seven years in the NFL, which means there are several candidates to experience this regression soon (or in Le’Veon Bell’s case, the regression has already started).

Potential 2021 Running Back Regression Candidates

| Player | Team | Total Rushes | Years in League | RYOE Per Rush |

| Le'Veon Bell | Kansas City Chiefs | 1,676 | 8 | -0.1 |

| Ezekiel Elliott | Dallas Cowboys | 1,507 | 5 | 0.43 |

| Derrick Henry | Tennessee Titans | 1,352 | 5 | 0.63 |

| Latavius Murray | New Orleans Saints | 1,261 | 8 | 0.06 |

| Carlos Hyde | Jacksonville Jaguars | 1,202 | 7 | -0.1 |

| Devonta Freeman | New Orleans Saints | 1,114 | 7 | -0.06 |

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.