Following the success of the Legion of Boom in the early 2010s, football organizations have tripped over themselves trying to get a piece of the Seattle Seahawks‘ single-high safety pie. And even though PFF only has coverage data dating back to 2015, we can still see that the NFL is firmly entrenched as a one-high league — 60% of all passing snaps over the past six seasons have come against single-high defensive looks.

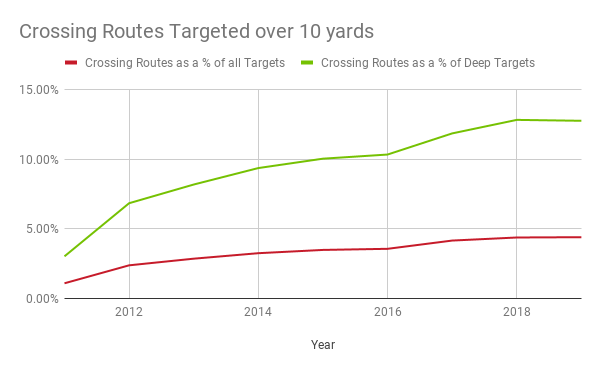

With the prevalence of these single-safety looks, offenses have come to adjust their routes and concepts to defeat these coverages. And one route family that has seen its target rate slowly but steadily rise is the deep crossing, or over, route:

This route starts on one side of the field and, in a perfect world, makes its way to the opposite sideline about 18-22 yards downfield. The ball is usually thrown before the receiver hits the sideline, however.

Because the route crosses the field, it can be a winner against either man or zone coverage. Against zone coverage, it can get lost behind the heads of the linebackers and in front of the safeties who are in backpedal mode. And the linebacker or down-safety who ends up being the zone defender to where the route ends up will often not be cognizant of a receiver who was lined up on the opposite side of the formation.

Against man coverage — and often against outside leverage by the coverage player — the receiver can get on his horse and have time to run away from the defender.

Both one- and two-high coverages have their versions of zone and man coverages, but the reason why the deep crossing routes work best against single-high defenses, whether they be zone or man, is directly correlated to the play of the safeties — 76% of all deep crossing routes are thrown against one-high defenses. That’s a hefty amount.

The safety dichotomy is the major player here, and we can see that defenses have a ready-made plan for taking away this route in two-high. With a safety on either side of the NFL hash marks, the opposite-side safety is in a perfect position to drive down on the crosser:

The safety already has leverage against where the route is going. The half-field safety can therefore play a little more flat-footed and doesn’t have to force himself to get too deep because he’s insulated by both the other safety and the cornerback to his side. Of course, in this example, it would have helped if they took the blindfold off Andy Dalton before he took the snap.

The single-high safety has no choice but to dive deep into the middle of the field as the lone centerfielder, allowing the crosser to run underneath him.

Offenses have developed a few different concepts that they’ll use to protect this valuable route. Mostly found at the college level, there's the Y-Cross:

This allows the quarterback to work the frontside combinations before resetting his feet to find the crossing route. It’s become a staple of many Air Raid teams, and it can usually be found wherever Chip Kelly resides.

The NFL has gone a step further and protects the crossing route with a post route from the opposite side, and this is the way most teams are trying to get the crosser open. The vertical route has a specific reason for being tagged into the play based on how defenses are saving themselves from being completely engulfed by a crossing route.

The response from single-high safety teams is to have someone, be it the safety or the cornerback, jump on the crossing route and pass the deep vertical route off to another player.

If the cornerback sees the crossing route coming into his vision as he’s carrying the vertical route from the receiver lined up in front of him, he can pass his route to the safety who is already in an inside alignment to take away a post route.

The safety could also take away the crossing route by jumping down on the route. This forces the backside cornerback to pick up the slack and hustle over the top of the deep vertical route from the opposite side. The New Orleans Saints made a nice play here on this concept against Carson Wentz in 2018:

The offenses from the old Mike Shanahan tree try to free their crossing route with a corner route instead of a post, and they’ll use it off play action. Overall, 54% of all deep crossers were thrown after play action in 2019 — and 55% of them were thrown off play action over the last six seasons — but that number is 81% with the San Francisco 49ers, 71% with the Los Angeles Rams, 62% with the Tennessee Titans and 83% with the Minnesota Vikings. All those teams run a very similar offensive system.

The corner route doesn’t allow the cornerback to come off that route to attack the crossing route, and the play action forces the linebackers to step up and honor the run, thereby giving more room for the crosser. They will also cut down the split of the receiver running the crossing route so he can get across the single-high safety’s face quicker and prevent him from jumping down on the route.

A nifty concept that pro teams have dabbled in recently is sending two vertical routes opposite the crossing route. This doesn’t allow the cornerback or the safety — whether it’s a single-high safety or a half-field safety — to come off their own routes and attack the crossing route.

The best receivers in the league make up the list of receivers with the most “open” and “wide open” deep-crossing catches. Julian Edelman, DeAndre Hopkins, Julio Jones, Keenan Allen and Travis Kelce make up the top five.

The mechanics of the route change depending on the use of play action and whether it goes up against man or zone coverage.

Here, Edelman lulls his defender to sleep because of his crafty route-running and the added time benefit of play action:

And as Hopkins gets into his route below, he feels it’s man coverage but the defender is off by a few yards. With the separation already in hand, he breaks quickly and flatly to the sideline to speed away from cornerback Jalen Ramsey.

Against tighter man coverage, setting the defender up by staying vertical as long as possible helps. Watch Edelman in the slot:

Another move to get free versus man coverage is the stair step. Instead of a few vertical steps, it’s just a quick shake upwards before coming back at the angle needed to get across the field. Justin Jefferson shows us how it works, even though he probably didn’t need to use it on this particular play:

Against zone, which is when most deep crossing routes are thrown — 55% of them have been thrown against zone over the last six seasons — you would ideally have your player continuing to gain ground as he comes across the field to get away from the backs of the linebackers. We can see Hopkins do this here:

A closer look:

With more teams going to the Shanahan-style wide-zone offense, we could see the popularity of these routes skyrocket in the coming years until the inevitable shift to a Quarters (two-high) landscape will cause another change in the offense vs. defense dynamic.

© 2026 PFF - all rights reserved.

© 2026 PFF - all rights reserved.