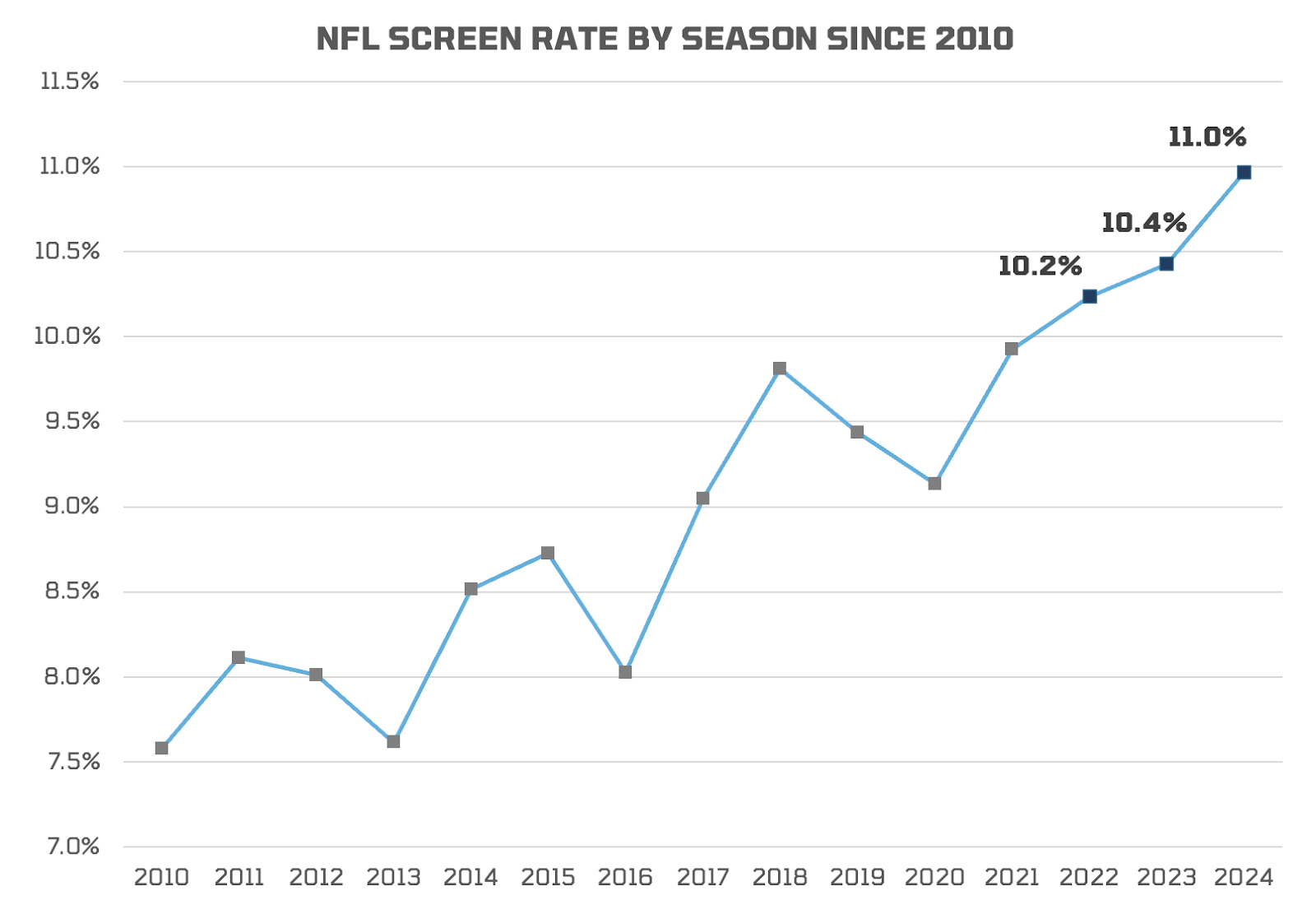

- The league-wide screen rate has reached a new high: Last season's 11.0% clip marked the third straight year of the NFL surpassing a 10% screen rate.

- But, why? Screens aren't actually producing more league-wide value than before. So, we're diving into how NFL coaches think and why teams are leaning more on those plays.

- Subscribe to PFF+: Get access to player grades, PFF Premium Stats, fantasy football rankings, all of the PFF fantasy draft research tools and more!

Estimated Reading Time: 7 minutes

“It’s an extension of their run game.”

You’ve likely heard that line when watching an NFL game — the broadcaster referencing how an offense uses quick passes or screens to pick up “easy” yards. And if you’ve heard it more often recently, that’s because teams are turning to screens at a higher rate.

More than 10% of total dropbacks across the NFL have been screen attempts in each of the past three seasons. The 2022 campaign was the first time the average sat above that threshold, and it has only continued to rise over the past two years.

One might assume screen usage is going up for the obvious reason: NFL teams are having success with it. But that hasn’t necessarily been the case.

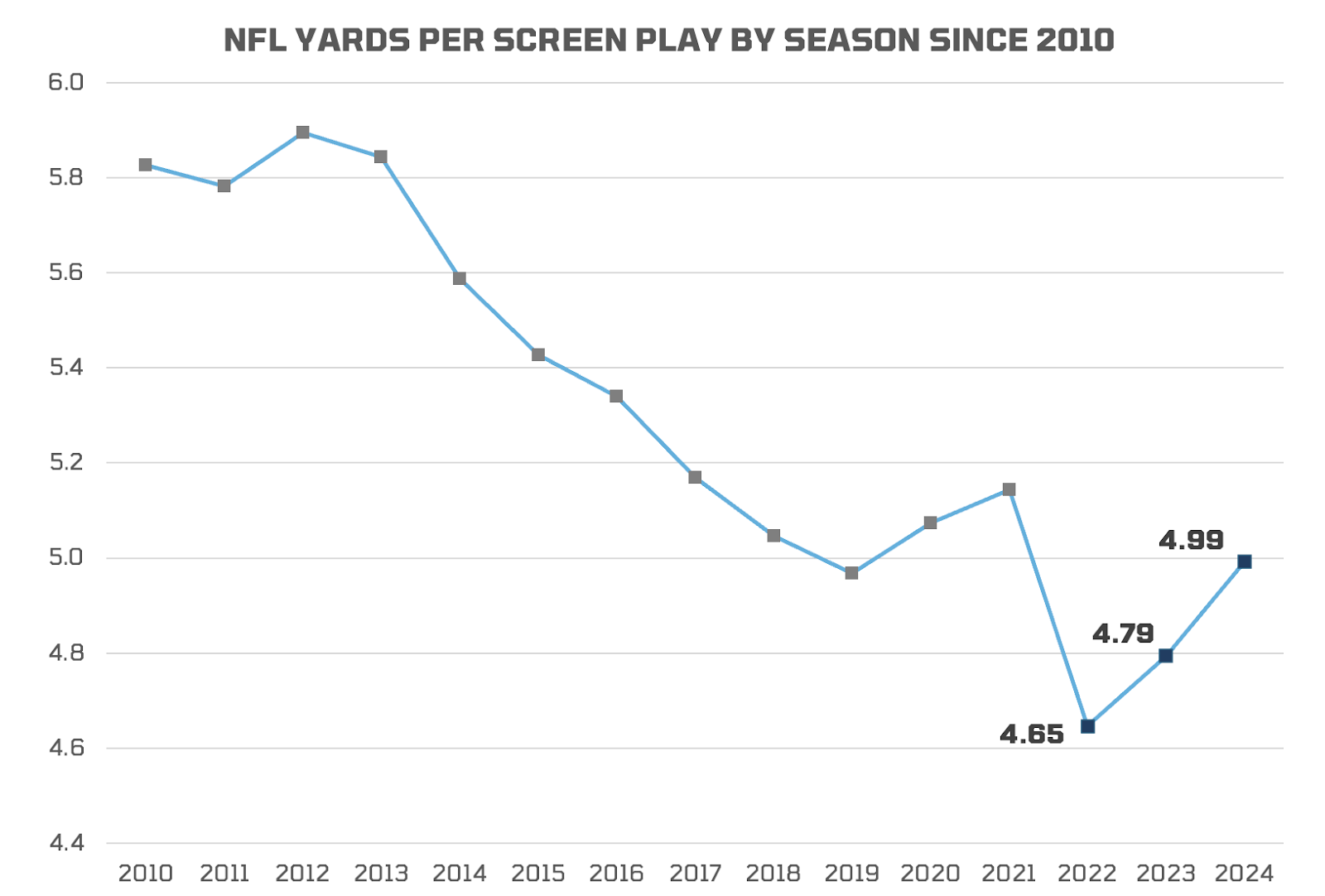

Ignoring some of the peaks and valleys in recent seasons, the general trend of the graph above shows declining production on screens. Three of the four seasons in which NFL teams have collectively averaged fewer than 5 yards per screen since 2010 have come in the past three years.

That begs the question: Why have we seen a steady rise in screen passes in recent seasons despite the play becoming relatively inefficient at a league-wide level?

We’ll start by attempting to get into the psychology of why NFL coaches call certain plays — an admittedly dangerous game to play.

Eric Eager, my former colleague and the current Vice President of Football Analytics for the Carolina Panthers, wrote about the value of perfectly blocked runs for PFF in 2021.

Eric wrote, “If a run play is perfectly blocked up (using PFF grades), the running game itself is more efficient than the most efficient offenses in the NFL … a perfectly blocked-up running play is more effective than a perfectly blocked-up passing play on average, and the results are ‘smooth,' as there isn’t the equivalent of an incompletion in their world.”

Offensive coaches in the NFL have an innate belief in their ability to call the right plays and execute at a high level. In other words, they believe their team can beat the averages of roughly one in three plays being perfectly blocked. That’s relevant in this piece because, in theory, screens are the pass-game extension of a run call.

Completion percentage on screens (86.0% in 2024) is significantly higher than on non-screens (62.5%), so you’re mitigating some of the negative play risk that comes with incompletions in the dropback passing game. You’re also less likely to take big negative plays, such as sacks and interceptions. And when screens are completed, a talented player sometimes needs to make only one defender miss in space to create a chunk play.

The overall EPA per play averages by play type in the NFL last season don’t do anything to say that screen plays aren’t a pass-game alternative to the run game. Teams added the same amount of expected points on average on screens as designed runs in 2024 — both of which were less efficient than the dropback passing game.

EPA Per Play Averages by Play Type in the 2024 NFL Season

| Play Type | EPA Per Play |

| Non-Screen Dropbacks | 0.05 |

| Screen Dropbacks | -0.08 |

| Designed Runs | -0.08 |

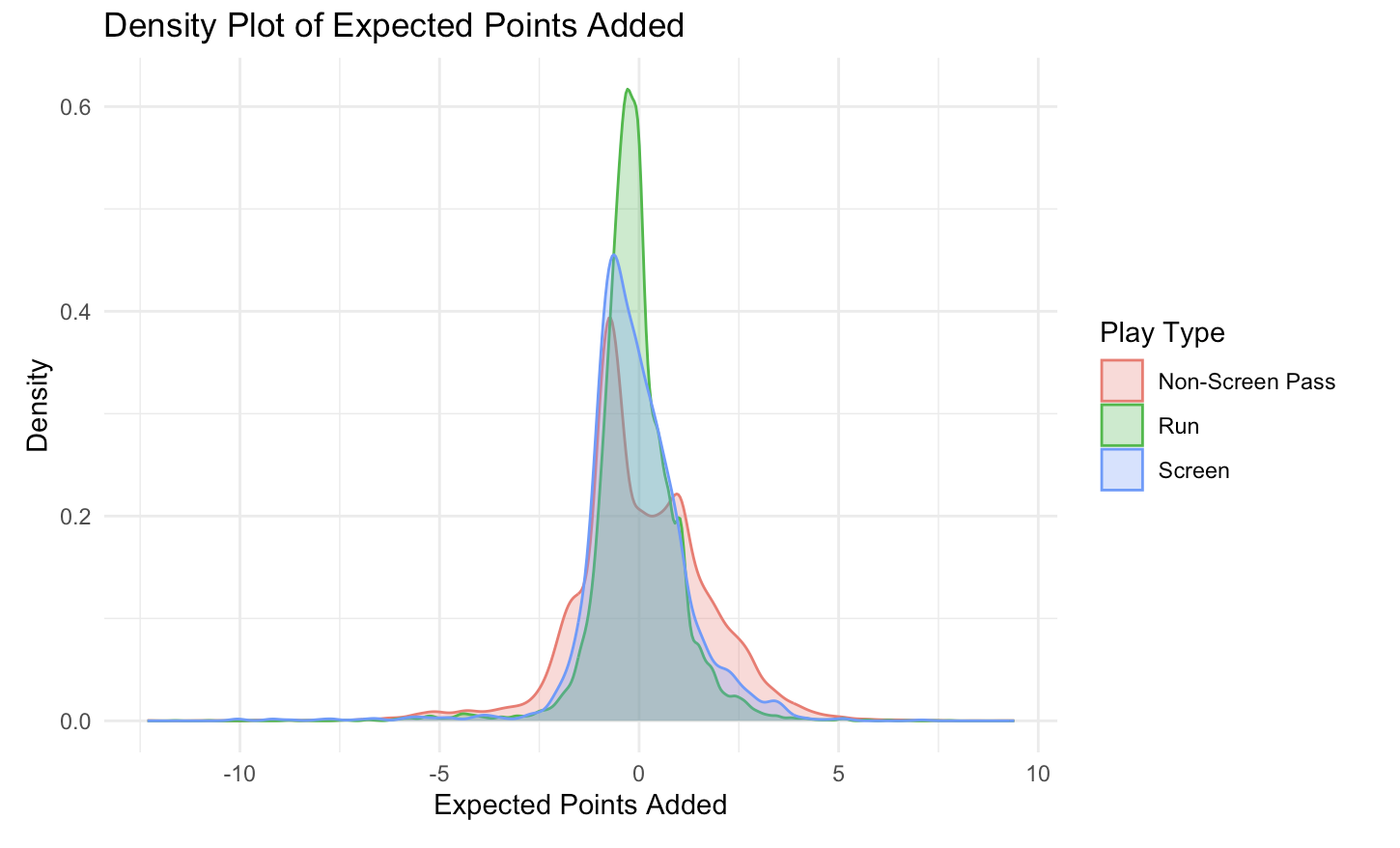

The distribution of EPA for those play types sheds a little bit more light on the range of outcomes for each, compared to simply looking at the point estimate of the average.

We can see that the distribution for run calls is more concentrated than other play types, with that peak coming just below zero expected points added. As one might expect, non-screen passes have a wider distribution with more chances for big swings in expected points in either direction.

The distribution for screen passes sits somewhere in between, with a peak slightly below that of run plays but with slightly higher chances at a big, positive gain. We can view those big negatives and big positives through the framework of EPA values of -1 or lower or +1 or higher.

“Big” Positive and Negative Plays by Play Type in the 2024 NFL Season

| Play Type | % of EPA < -1 | % of EPA > 1 |

| Non-Screen Dropbacks | 19.4% | 27.1% |

| Screen Dropbacks | 14.1% | 14.8% |

| Designed Runs | 9.6% | 11.8% |

While it may seem like screens can “replace” runs in the sense of providing a break where the offense is mitigating the risk of a negative play, the quarterback isn’t tasked with making reads and more difficult throws downfield and the offensive line doesn't need to hold up in pass protection for 2.5-plus seconds, it isn't necessarily a one-for-one comparison.

Screens sit almost exactly between designed runs and non-screen dropbacks in the percentage of plays with an EPA generated below 1.0, and while there is slightly more upside for a big play, screens don’t come close to touching the 27% of non-screen dropbacks that generate an EPA mark above 1.0.

Even looking strictly at situations where the expectation is that screens will be more successful — such as when the defense blitzes and the offense has the opportunity to get blockers in space with fewer players back in coverage — offenses didn’t prosper often last season.

EPA Per Play Against the Blitz by Play Type in the 2024 NFL Season

| Play Type | EPA Per Play |

| Non-Screen Dropbacks | 0.02 |

| Screen Dropbacks | -0.15 |

| Designed Runs | -0.13 |

On average, offenses were more efficient when running into blitzes than when calling a screen pass during the 2024 season.

A well-executed screen thrown into a void left by a blitzing defender is one of the more beautiful plays in football. But some parallels can be drawn between that and perfectly blocked run plays. The numbers indicate that it happens less than we would like to believe.

This isn’t to say that offenses aren’t executing screens at a high level. The Detroit Lions, Tampa Bay Buccaneers and Arizona Cardinals all averaged at least 0.2 EPA and 6.5 yards per play on screen passes last year.

The Buccaneers, specifically, utilized screens often and effectively in 2024 under then-offensive coordinator Liam Coen. Tampa Bay ranked fourth in the NFL in screen usage (17.0% of dropbacks) and second behind only the Detroit Lions in EPA per screen (0.257). That type of efficiency has become more the exception than the baseline, yet screen rates continue to climb across the league.

A lot of words have been written about pass game versus run game efficiency, and a lot of the “just throw the ball” conversation has grown tiresome. Building the ship out of solely dropback passes isn’t realistic. An offense needs to have variety to keep defenses off balance, and dropping back on every snap strains the players who drive pass-game production.

Parallels can be drawn to the NBA, where when a player's usage goes up, it’s difficult for them to maintain the same level of efficiency compared to a lower-volume role.

Anecdotal evidence supports the idea that offensive linemen would rather be proactive in the run game and impose their will rather than play reactively in pass protection.

This all points to a world where a rising screen rate makes sense; it’s a compromise between the more efficient pass plays and the “safer” runs, where a well-executed play still offers some upside. The issue is that screens, on average, aren’t any more efficient than running the ball and still carry more downside.

In the cyclical nature of football, it seems like we’re reaching a point where run rates could increase with teams playing more two-high coverage shells due to trying to take away explosive passes. That was, in many ways, the story of the 2024 NFL season, with veteran running backs Saquon Barkley, Derrick Henry and Josh Jacobs as key components on new teams.

It's worth watching next season whether that trend pushes screen rates down from the 11.0% clip in 2024, or whether that number continues to climb despite falling efficiency.

© 2026 PFF - all rights reserved.

© 2026 PFF - all rights reserved.